Ancient Egyptian Medical Practices We Still Use Today

Ancient Egypt is mostly recognized for its pyramids, hieroglyphs, and mummies. A rich culture that lasted for over 3,000 years before Christ, it left behind tons of relics, which provide insight into the civilization. Thanks to translations of documents and inscriptions as well as beautiful images, we know a lot about ancient Egyptian life. Thanks to the ancient Egyptians’ practice of mummification, they learned much about the human body and seem to have developed advanced medical knowledge. Centuries ahead of their time, a lot of the practices that doctors used in ancient Egypt would not be unfamiliar to us today. Doctors may no longer use spells and amulets as the ancient Egyptians did, but in many other ways, a visit to the doctor’s office may not have been so different thousands of years ago.

Taking A Pulse

When we walk into a doctor’s office today, there are a few things that get checked every time, namely blood pressure, temperature, and pulse. The pulse can grant insight into the health of the circulatory system. Yet to understand it, there first needs to be an understanding that arteries and veins run throughout the body. This is common knowledge today, but for early medicine, it was a huge breakthrough.

Likely as a result of their mummification practices, ancient Egyptians had knowledge of the circulatory system. They understood its connections throughout the body and that it carried this “pulse.” They did miss one factor in that they didn’t seem to know that the heart itself is a pump. They saw it as a reservoir for the blood. Nevertheless, they knew the importance of the vascular system and were able to use it to help treat and diagnose illnesses.

The idea of measuring a pulse was far ahead of its time, and it would be centuries before it was picked up elsewhere in the world. In their knowledge of the vascular system, the Egyptians also counted the number of vessels reaching each part of the body. Their numbers were not accurate, however, as they didn’t realize how tiny arteries and veins become. But their counting may have allowed them to locate larger blood vessels, which would have been useful in case of injury or during surgery to stop bleeding.

Turn Your Head And Cough

Yes, men have been enduring this awkward exam for centuries, it seems. The Ebers Papyrus, a medical manual from ancient Egypt, mentions the diagnosis of a hernia, stating it is a “swelling appearing on coughing.” There are even images from ancient Egypt of figures with both umbilical hernias, which protrude from the stomach, and the all-too-graphic images of hernias in the scrotum.

Hernias happen when part of the bowel protrudes through the stomach’s muscular wall. They’re often caused by straining or lifting heavy things. Considering that the Egyptians gave us massive stone monuments like the pyramids, they were accustomed to lifting heavy things and may have been very familiar with hernias.

Their treatment for hernias, however, seems less known. The Ebers Papyrus does mention using heat on the area, but it’s not entirely clear if the heat is meant to be just a soothing treatment or if it refers to cauterizing the area to seal the muscles after minor surgery. With so many images of people living with hernias, one could wonder if they were even treated at all.

Tampons

Many would assume that tampons are a modern advancement that gives a woman on her period freedom. It is true that tampons were not used until recently in many Western cultures. There were even advertising campaigns as late as the 1980s touting the benefits of tampons and trying to convince American women that they were safe. These campaigns even referred to the ancient Egyptians’ use of them as proof that they are ancient and natural.

Often referred to as a tyet or an Isis knot, cloth tampons were made by using scrap fabric, often cotton, rolling it up, and tying a string around the center. The name “Isis knot” refers to the goddess Isis, who according to legend, used a tampon while pregnant with Horus to protect him while in the womb from attacks by the god Seth. Ancient Egyptians also used other cloths similar to today’s pads, which was common throughout many early cultures. Yet the benefits of the supposedly modern tampon may be something that Egyptian women knew all about.

Fillings

Cavities were actually rare in ancient Egypt. Since sugar wasn’t a part of the Egyptian diet, they did not have the tartar development and other issues that we do now. They did, however, wear their teeth down. Flour and grains were ground with stone, and despite their best efforts, small pieces of stone were always in the food. Living in a sandy desert likely added some grit as well. This wore down the teeth and could lead to cavities or infection. These infections could actually lead to death if the bacteria entered the bloodstream. Nefertiti’s sister, Horembheb, supposedly suffered from bad teeth and had lost all of them by the time of her death, likely due to infection.

Different fillings and ointment recipes are found in the Ebers Papyrus. One describes how to treat “an itching tooth until the opening of the flesh: cumin, 1 part; resin of incense, 1 part; dart fruit, 1 part; crush and apply to the tooth.” The idea was that this would drain the infection. Other filling recipes included honey, which has antibacterial properties, and ocher, a paint pigment heavy in iron, and ground wheat. Other times, the filling was simply cloth.

In 2012, a mummy was CT scanned, uncovering a cavity that had been filled with linen. The man was still suffering from the infection at the time of his death, however. Ancient Egyptian doctors did their best to treat cavities and to stop them from getting infected, but going to the dentist was never any fun.

Prostheses

Mummies in Egypt have been found with the world’s oldest known prosthetic limbs, toes, fingers, and so on. Prostheses to replace missing parts was essential to Egyptians for a couple of reasons. One was the Egyptian belief that after death, the body needs to be whole and preserved for them to be able to return to it in the afterlife. This is why mummification was so important and likely why prostheses existed. By replacing the lost limb, the body would be made whole again.

Of course, having a prosthesis would help a person maintain some functionality in life, and there is evidence that prostheses were also made for living patients. This shows how Egyptians used amputation to treat infections and injuries, and it appears that people sometimes survived the surgeries. The most famous of these patients was a lady found with a wooden big toe. The area under the prosthesis had healed, showing that she actually used the prosthetic toe in life. It likely helped her walk and balance once the old toe was lost. It is considered the oldest known prosthesis ever discovered.

Government-Controlled Medicine

Access to medical care was very well-controlled by the ancient Egyptian government. Doctors were educated through a specific curriculum and were members of a “house of life,” which was usually was associated with a temple. These were medical institutes that trained doctors and also functioned as medical practices where anyone could go to receive treatment.

Also, as mentioned before, there were medical manuals like the Ebers Papyrus and the Edwin Smith Papyrus, in which ailments and their treatments are outlined as well as recipes for medicines. This shows us that doctors shared cures and treatments as a part of standardized care. Doctors in ancient Egypt could be male or female and appear to have chosen specialties, much like our doctors do today. With access to well-trained doctors, Egyptian citizens had better health care than almost anyone else at the time.

Even workers’ compensation seemed to exist. There are descriptions of medical camps set up near construction projects and quarries so that injured workers could receive treatment. It appears that if the injury occurred on the job, the employer would cover the cost of care. Workers could even receive supplemental pay if they were unable to work. Thousands of years ago, this was a very complex way to approach health care and is amazingly similar to how we look at it today.

Prescriptions

Having to take your medicine is apparently as old as civilization itself. Thankfully, now we have a spoonful of sugar to help it go down. The ancient Egyptians weren’t so lucky. Often, medicines were trial and error. Some things ended up working really well. Others may have done more harm than good.

The Egyptians knew that honey worked well on wounds. (It’s still used today for skin ailments.) They also knew that mint could calm a stomach. Yet other items like lead and feces may not have been such great ideas. Whether they worked or not, there are dozens of recipes for medicines preserved in the medical papyri, along with instructions for their dosage and use. Patients in ancient Egypt would have been sent home with these concoctions and instructed on how to use them just as we are now.

There were medications for all sorts of issues, made from a wide variety of materials. Minerals like copper, clay, lead, and salt were used. Herbal remedies included fennel, onion, linseed, and mint. Other (lets call them “organic”) items included hair, skin, blood, feces, and more from various animals and even humans. These elements were usually combined in recipes for the fullest effect. There seem to have been many recipes for constipation. Some advise simply eating more figs (not so bad), while others prescribe castor oil, which we still use today, mixed with cold beer. A remedy for tapeworm contains equal parts lead, petroleum, ta bread, and sweet beer. It may have worked to kill the tapeworm—and hopefully not the patient.

Poultices were also a very popular treatment, with external concoctions applied for everything from baldness to stomachache. Milk was common in these, as were multiple kinds of dung, from cow to sheep to goose. Clays and lead are often included as well. Human secretions were sometimes included, from urine to milk to blood. In the case of anxiety, one cure states to rub the afflicted person down with the “milk of a woman who has born a son.” It’s not clear it if it worked.

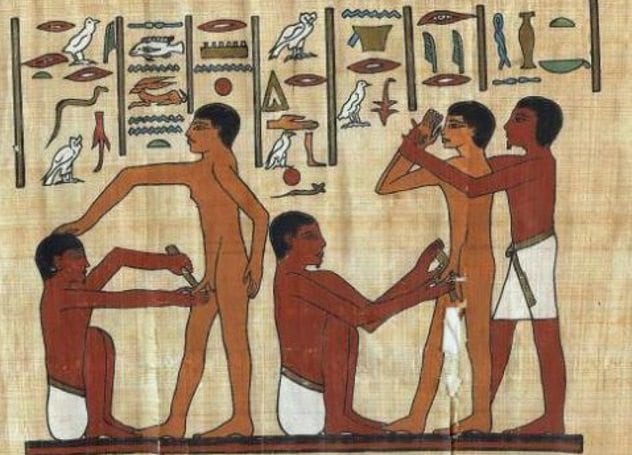

Circumcision

The practice of removing a male infant’s foreskin has come in and out of vogue over the centuries, sometimes viewed as a religious practice and other times as medical. For centuries, the Jewish culture was identified with this practice, as Christians did not use it. Today, is is widely practiced by doctors in most Western countries regardless of religion. The ancient Egyptians seem to have practiced circumcision widely. Images show doctors performing the procedure on patients. Egyptians were very interested in personal hygiene and often shaved off their body hair to stay clean and avoid parasites and conditions associated with uncleanliness. This may be what led them to start practicing circumcision throughout the culture. Circumcision was so common that uncircumcised penises were actually a novelty. Writings describe soldiers’ fascination with the uncircumcised penises of the conquered Libyans, often collecting them from the slain to bring home and show off. Thankfully, that practice has been lost.

Surgery

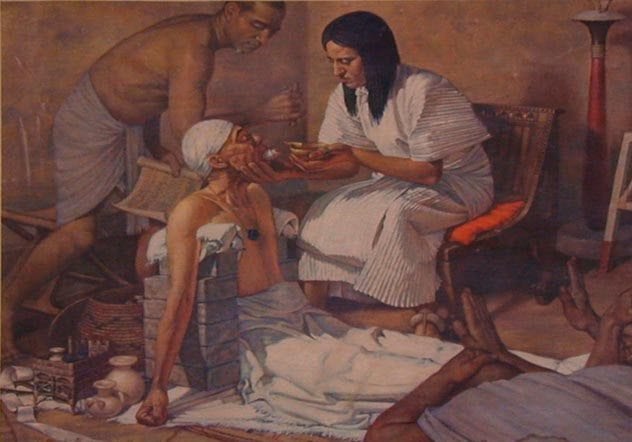

The ancient Egyptians gained a wealth of knowledge of human anatomy and the workings of the body through their mummification practices. By operating on the dead, they were able to see issues in bodies and make associations with illnesses in life. These skills allowed them to practice surgery. Later cultures in the Middle Ages would lose this knowledge completely, as autopsies were illegal for religious reasons. Their willingness to cut into a body put the Egyptians centuries ahead medically.

Many mummies show surgeries that actually healed, from trephination to the removal of tumors. Scalpels used for surgery were either copper, ivory, or obsidian. Obsidian was particularly special, as it is a volcanic glass that keeps an edge better than most modern metal and is still used today. Patients were given alcohol and sedatives before a procedure, and since anesthesia didn’t exist, one could only hope to pass out. Mandrake root could be used as a sedative, and poppy juice, an opioid, was used for pain management. The main issue with survival rates was that without the knowledge of blood transfusions, patients would often bleed out if the surgery was too complicated or too long. Cauterizing vessels with hot blades helped slow the bleeding. After surgery, antibiotic ointments such as honey and copper helped stave off infections. The patients who survived their ordeals may have been the first in history to have undergone medical surgery.